Breaking News

Toxic mix of betting, social media fuels athlete abuse

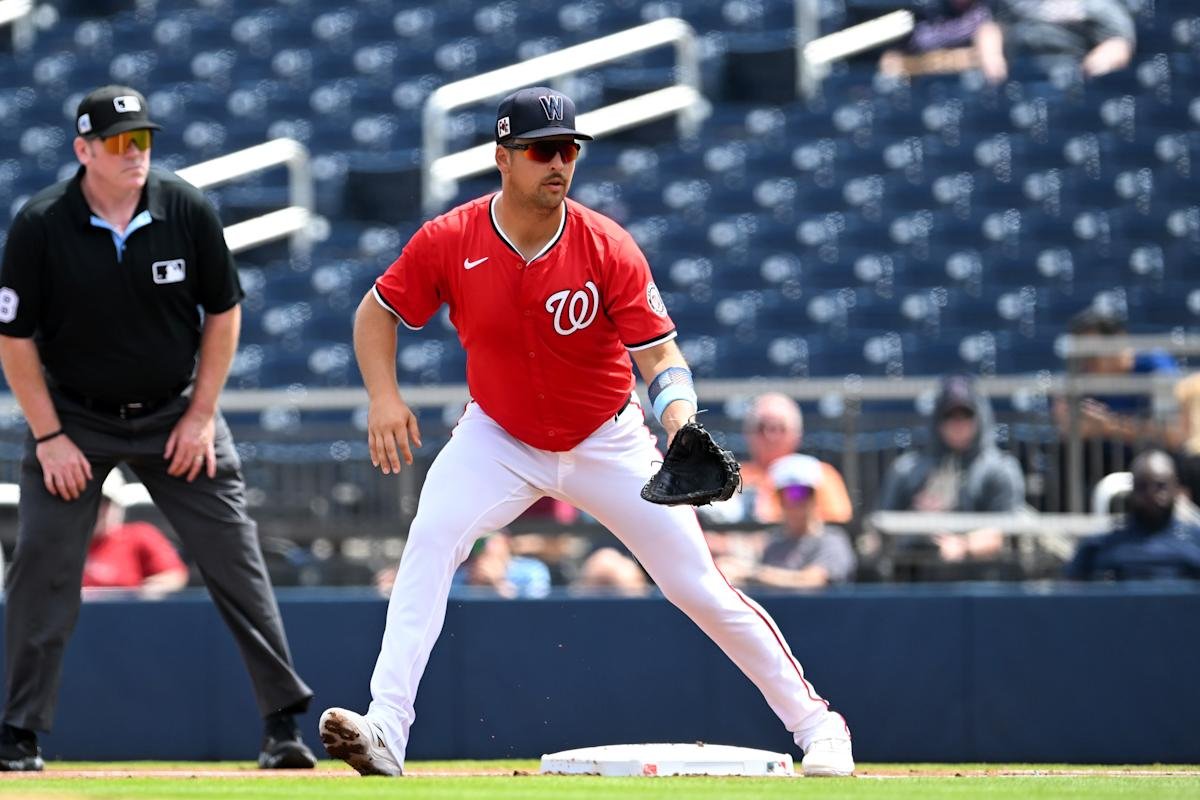

Many nights after work, as people often do, Washington Nationals first baseman Nathaniel Lowe checks his social media accounts. Unlike most, however, Lowe must brace himself to find out which anonymous trolls, miscreants and provocateurs, at that very moment, want him dead.

If the safe-word filters on his accounts do their job that night – and if Lowe happened to have excelled at his job, at least relative to the prop bets staked to his performance – the abuse might not be so bad. Otherwise?

Subscribe to The Post Most newsletter for the most important and interesting stories from The Washington Post.

“‘Kill yourself’ shows up pretty often,” said Lowe, who has won a Gold Glove, a Silver Slugger award and a World Series in his career. Those kinds of messages, he added, are there “five days a week.”

Like many athletes, Lowe, 29, has come to view the nightly stream of online vitriol as another annoyance inherent to his line of work, no different from late-night flights and professional autograph-seekers.

“Like, that’s just what you kind of sign up for,” Lowe said. “And that’s what gambling has brought into the game.”

But in recent months, as online sports betting continues to expand in the aftermath of a landmark 2018 Supreme Court ruling – Americans legally wagered a record $147.91 billion on sports last year – the problem of online threats and harassment of athletes by gamblers appears to have become more widespread, more specific and more sinister, alarming many in the sports industry, not least of all those on the receiving end.

“I understand people are very passionate and … love sports,” veteran Houston Astros pitcher Lance McCullers Jr. told reporters recently, after detailing death threats made against him and his family that were later traced to a bettor overseas. “But threatening to find my kids and murder them is a little bit tough to deal with.”

Famous athletes have long been subjected to verbal abuse by angry partisans, as any NFL kicker who’s missed a game-winning field goal, or any major European soccer player who has missed an overtime penalty kick, can attest. Horrifying incidents between athletes and deranged fans is nothing new, either, with the on-court stabbing of tennis star Monica Seles in 1993 perhaps the most vivid example.

But what is happening now, to athletes of all degrees of fame, feels like a distinctively modern problem, resulting from an explosive mixture of forces: the exponential growth, financial might and cultural penetration of the sports-gambling industry; the AI-driven ability of that industry to deliver rapid, in-game gambling products via mobile devices; and the ubiquity of social media and the anonymity it provides while obliterating the barriers between athletes and fans. The dynamic is exacerbated by socioeconomic trends, such as the widening economic chasm between fans and athletes and the rampant disaffection sociologists have identified in young, online males.

“People get this idea, like, ‘This big baseball player, making a great amount of money. … I see them out there living their lives happily with their family, while they’re pitching poorly,’” said Nationals pitcher Josiah Gray. “So they say, ‘You shouldn’t be living happily with your family. You should be lamenting on your rough outing or your rough day at the plate.’ And then trying to ruin your day that way. It’s more [about] psychology and how players are easily accessible [through] social media.”

It is now commonplace, in fact, for gamblers to track down an athlete’s Venmo account and request money to cover the cost of a lost bet, often including a nasty or threatening message with their invoice. Occasionally, but far more rarely, an athlete picks up their phone to find a “tip” has been sent to their Venmo as thanks for a winning performance.

“That’s why I had to get rid of my Venmo – because I was either getting paid by people, or people requesting me a bunch of money when I didn’t win. It wasn’t a good feeling,” golfer Scottie Scheffler said this week. Asked what was the most money a gambler even sent him, the three-time major champion replied, “I don’t remember. Maybe a couple bucks here or there. That didn’t happen nearly as much as the requests did.”

Although little data exists to demonstrate the extent of the problem, recent polls and studies, as well as anecdotal evidence, suggest it is affecting athletes across the entire sports spectrum with increasing frequency.

A December study by four of the biggest tennis federations in the world found that angry gamblers were responsible for nearly half of the 12,000 abusive social-media posts directed at tennis players that year.

A May 2024 NCAA study during that year’s men’s and women’s March Madness events found more than 4,000 instances of threatening or abusive social-media posts or messages directed at athletes, with women three times as likely as men to be on the receiving end. (A subsequent NCAA-commissioned study of the 2025 tournaments, however, noted a 23 percent decline from 2024 in gambling-related abuse.)

And when The Athletic, in an informal poll this spring, asked 133 baseball players whether legalized sports betting has “changed how fans treat you or your teammates,” 78 percent answered yes.

Even athletes who at one time might have toiled in relative anonymity, such as offensive linemen and backup catchers, are now fair game to disgruntled bettors on the wrong end of a losing “prop bet,” placed on something as specific as a basketball player’s rebound total or the first player in a football game to score a touchdown.

“It’s definitely getting worse and worse – through every social media, people being in your DMs with death threats,” said Detroit Tigers backup catcher Jake Rogers, who said he has received death threats as recently as earlier this season despite having had only 48 plate appearances as of Friday. “… You can ask every single guy in here, and they’ve gotten a really bad one, probably in the last week.”

Those types of findings do not surprise those who study the problem and those who are tasked with combating it.

“The speed of gambling, the intensity of gambling – they’ve increased exponentially. We’ve fundamentally changed the way people gamble,” said Harry Levant, a certified gambling counselor and director of gambling policy with the Public Health Advocacy Institute at Northeastern University. “Then, social media creates this idea of anonymity. … We shouldn’t be quite so surprised when we see an increase in the number of people demonstrating antisocial behavior.”

Levant and others in the problem gambling space have singled out the rise of “microbetting” – small, fast-moving, in-game wagers, delivered with the help of AI systems, on everything from the velocity of the next pitch in baseball or the outcome of the next play in football. Those bets, they say, are fueling the rise in gambling addiction, with all its attendant problems, including threatening behavior toward athletes.

“If you deliver a known addictive product to people at light speed with technology in this way, you are going to cause harm to people, and [those] people will take that harm to lengths of desperation,” Levant said.

Asked to respond to comments from Levant and others, Joe Maloney, senior vice president of strategic communications for the American Gaming Association, said in a statement: “The outcome of a bet is never an invitation to harass or threaten athletes, coaches, or officials. Abuse of any kind has no place in sports. The legal, regulated industry offers the transparency and accountability needed to identify bad actors and collaborate with leagues, regulators, and law enforcement to deter misconduct and enforce consequences.”

The gambling and sports industries have successfully prosecuted some gamblers who have sent death threats to athletes and their families. Most notably, in 2021, a prominent gambler named Benjamin “Parlay” Patz pleaded guilty to transmitting threats after investigators linked him to more than 300 threatening messages sent to the social media accounts of pro and collegiate athletes, saying, for example, “I will sever your neck open” and “I will kill your entire family.” Patz’s sentence included six months of home detention and 36 months of probation but no prison time.

Publicity of such cases “could deter” such behavior, said Jeffrey Deverensky, director of the International Centre for Youth Gambling Problems and High-risk Behaviors at McGill University in Montreal, who has authored studies for the NCAA on gambling. “But it doesn’t happen very often. It’s difficult to catch these people – especially via social media, because of the anonymity – unless they’re trying to influence the outcome of the game.”

The gambling industry is quick to highlight the role played by social media in contributing to the problem. The AGA’s Maloney pointed to a 2024 NCAA study showing only 12 percent of online abuse directed toward athletes was gambling-related, with the remaining 88 percent falling into categories such as racial, sexual or trans/homophobic abuse. (Knicks star Jalen Brunson is among the NBA players who have said they’ve faced racial slurs online.)

“Social media platforms,” Maloney said, “will absolutely have to be part of an overall solution to this problem.”

Many athletes, however, have all the anecdotal evidence they need to know what’s behind the rise in abuse. Most of them already had social media accounts before 2018; it was only after the landmark Supreme Court case and the explosion of legalized gambling, hastened by the 2020-21 pandemic that kept people indoors and drove them online, that the problem got out of hand.

“Gambling is definitely the main thing,” the Nationals’ Lowe said. “DraftKings sponsors broadcasts, and they have [signage] all over the stadium. BetMGM is all over the place. These big companies are obviously making a whole lot of money off the [sports gambling] industry.”

Increasingly, authorities and the problem-gambling communities are trying to curb the prevalence of threatening behavior through regulation, as well as services targeting gambling addiction and anti-bullying campaigns. NCAA’s “Don’t Be a Loser” spot ran frequently during this year’s March Madness tournaments, discouraging harassment toward athletes resulting from lost bets.

“You’re going to start seeing more problem-gambling prevention [advocacy] in middle schools and high schools, like you see drug-prevention and alcohol-prevention,” said Michael A. Buzzelli, director of problem gambling services for the Ohio Casino Control Commission. “And you probably won’t see a massive change in behavior until you do that – until gambling is looked at as just as addictive and just as problematic as alcohol and drugs.”

Ohio is one of 15 states that bans prop bets on college athletes, and this spring, the NCAA called for a nationwide ban on athlete-specific prop bets in states with legal sports gambling. “You have kids who have had thousands of [threats via social media] being directed at them during our tournaments,” said Charlie Baker, the governing body’s president. “Just getting prop bets out of college sports is a really important priority of ours.”

Aside from their association with threats, prop bets on individual athletes are also more susceptible to “game-integrity” issues, given the athlete’s unique ability to influence the outcomes of those bets.

But the AGA’s Maloney said that while the industry “isn’t standing in the way” of efforts to ban prop bets, such bans are likely to result in those wagers moving to unregulated or illegal betting markets.

“Regulated markets need to allow for growth and innovation,” Maloney said, “simply because we do compete with a vast, predatory and pervasive illegal market that has all the trappings of what a legal app, or in some cases what a legal physical space, would look like.”

In March, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Connecticut) and Rep. Paul D. Tonko (D-New York) reintroduced their bill, the SAFE Bet Act, that would, among other things, limit advertising for sportsbooks; mandate “affordability checks” to restrict the amount of money a gambler can wager in a specific period; ban prop bets featuring collegiate and amateur athletes; and prohibit the use of AI in creating products such as microbets.

The bill, Tonko said in a telephone interview, “speaks forcefully to the need to have guardrails or restrictions” on the sports gambling industry. “We don’t want to outlaw mobile sports gambling. But we’re trying to take a known addictive product and make it safer.” Still, he acknowledged their bill has a “tough journey” to passage.

In the meantime, athletes will continue to face an onslaught of vitriol on their social media accounts – unless, like many, they choose to delete those accounts, or, like veteran Baltimore Orioles pitcher Charlie Morton, never open any in the first place.

“Personally, I don’t think the world should have access to me, to say anything they want at any time to me,” said Morton, 41. “When you threaten to kill somebody or hurt somebody, you’re doing something illegal. I don’t know why you would subject yourself to an environment where that would be normal.”

But for younger players, or those who are naturally more online, or those whose marketing teams encourage them to do brand-building through socials, that leaves only a couple of options.

“Don’t look at it,” said the Nationals’ Lowe. “And play better.”

– – –

Jesse Dougherty, Nicki Jhabvala, Bailey Johnson, Adam Kilgore, Rick Maese and Mark Maske contributed to this report.

Related Content

He’s dying. She’s pregnant. His one last wish is to fight his cancer long enough to see his baby.

The U.S. granted these journalists asylum. Then it fired them.

‘Enough is enough.’ Why Los Angeles is still protesting, despite fear.