Lifestyle

Breakthrough study finds deficiency of this common nutrient could contribute to Alzheimer’s

A deficiency of the metal lithium in the body could be a key factor contributing to the development of dementia in Alzherimer’s patients, a groundbreaking new study reveals.

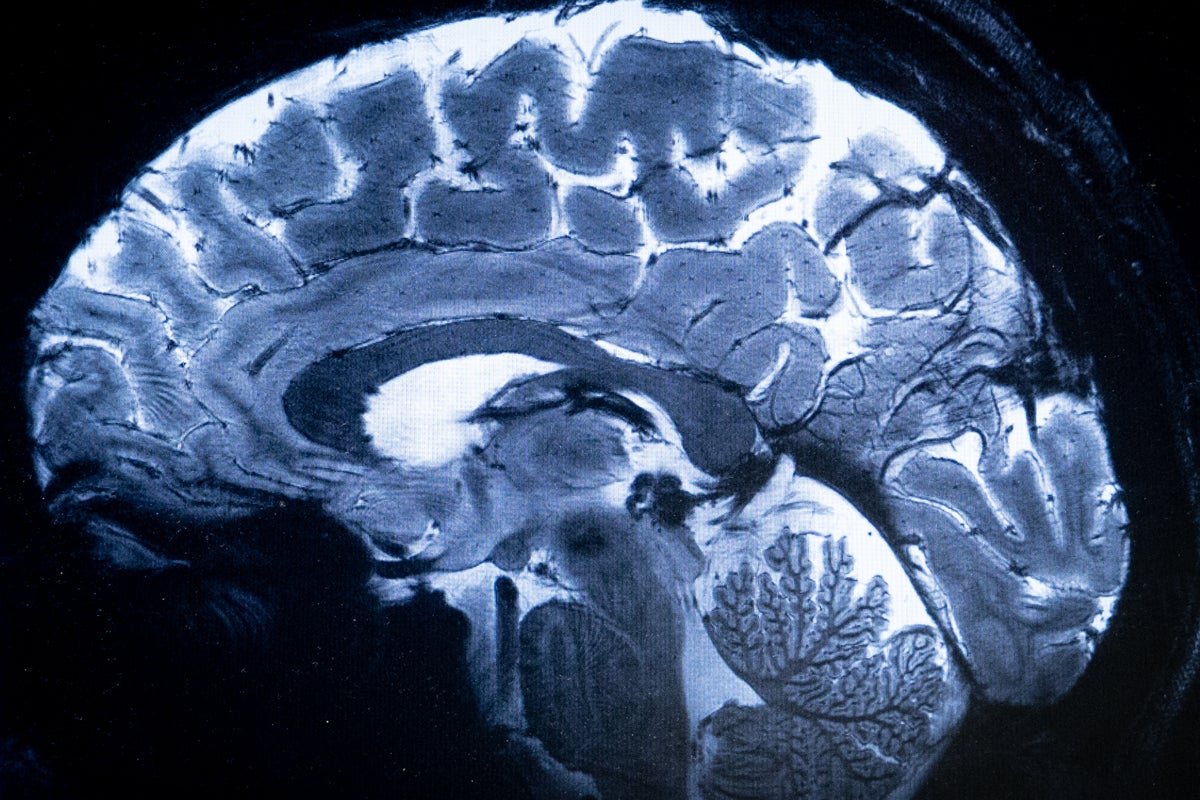

The decade-long research, published in the journal Nature, shows for the first time that lithium occurs naturally in the brain and maintains the normal function of all its major cell types, preventing nerves from degradation.

Scientists from Harvard Medical School found that lithium loss in the human brain is one of the earliest changes leading to Alzheimer’s, while in mice, a similar lithium depletion accelerated memory decline.

A reduced lithium level was found in some cases due to the metal’s impaired uptake and its binding to amyloid plaques, which are known to be smoking gun signs of Alzheimer’s.

Researchers also showed that a new type of lithium compound – lithium orotate – can avoid capture by amyloid plaques and restore memory in mice.

Top row: In a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, lithium deficiency (right) dramatically increased amyloid beta deposits in the brain compared with mice that had normal physiological levels of lithium (left) Bottom row: The same was true for the Alzheimer’s neurofibrillary tangle protein tau. (Yankner Lab)

In the study, scientists used an advanced type of mass spectroscopy chemical analysis method to measure trace levels of about 30 different metals in the brain and blood samples from a range of people, including cognitively healthy people, those in an early stage of dementia, and those with advanced Alzheimer’s.

The analysis revealed that lithium was the only metal with markedly different levels across groups, which also seemed to change at the earliest stages of memory loss.

“Lithium turns out to be like other nutrients we get from the environment, such as iron and vitamin C,” study senior author Bruce Yankner said.

“It’s the first time anyone’s shown that lithium exists at a natural level that’s biologically meaningful without giving it as a drug,” Dr Yankner said.

Although lithium compounds have been historically in use to treat a range of mental conditions like bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder, in these cases, they are given at much higher concentrations that could even be toxic to older people.

Lithium deficiency thinned the myelin that coats neurons (right) compared to normal mice (left) (Yankner Lab)

Scientists have now found that lithium orotate is effective at one-thousandth this dose – enough to mimic the natural level of lithium in the brain.

The latest findings with lithium orotate, however, needs to be confirmed in humans via clinical trials.

Yet, researchers suspect that measuring lithium levels could help screen people for early Alzheimer’s.

The findings revise the theory of Alzheimer’s disease, which affects nearly 400 million people worldwide, offering a new strategy for early diagnosis, prevention, and treatment.

Decades of studies have shown that Alzheimer’s disease involves an array of brain abnormalities, including clumps of the protein amyloid beta, tangles of the protein tau, and a loss of the brain’s protective protein REST.

However, these abnormalities have never fully explained the condition.

Lithium was the only metal that differed significantly between people with and without mild cognitive impairment, often a precursor to Alzheimer’s disease (Aron et al, ‘Lithium deficiency and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease’, Nature (2025))

For instance, it remains unclear why some people with Alzheimer’s-like changes in the brain never go on to develop dementia or cognitive decline.

Recent treatments developed to target amyloid beta plaques also don’t seem to reverse memory loss, only modestly reducing the rate of cognitive decline.

Now, scientists say lithium could be the critical missing link.

“The idea that lithium deficiency could be a cause of Alzheimer’s disease is new and suggests a different therapeutic approach,” Dr Yankner said.

“You have to be careful about extrapolating from mouse models, and you never know until you try it in a controlled human clinical trial… But so far the results are very encouraging,” he added.